How COVID-19 Sparked a Wave of Innovation at Otis College

Learning from the College’s move online last spring in the wake of the pandemic, Otis instructors were ready for their virtual classrooms this fall.

It might seem counterintuitive to explore a hands-on discipline like ceramics through a virtual classroom, but for Joan Takayama-Ogawa, working in clay has brought hope and peace of mind during these challenging times. In her Intermediate Ceramics course for BFA and Extension students, which she’s had to teach online due to public health restrictions in Los Angeles County, Takayama-Ogawa’s first assignment this semester involved students designing a “pandemic victory garden planter” made from terracotta clay, which requires only one firing and no glaze. “Because we are witnessing food insecurity throughout America and Los Angeles, I thought this assignment could help our students grow food in their apartments, homes, and residence halls,” she says. Generous donors provided each student with a clay kit, and for those without access to Otis’s ceramic studio—which is available by appointment to students to allow for social distancing—Takayama-Ogawa found alternate firing solutions for students who lived as far away as San Francisco and China. The assignment has produced such extraordinary work that once in-person classes resume at Otis, she plans to continue opening each semester with the Victory Garden Project.

Throughout Otis’s programs, from Architecture/Landscape/Interiors to Toy Design, Creative Action to Foundation, changes in technology and practice are creating new skills and opportunities for students and faculty alike. Computing capacity has greatly increased during the remote semester, allowing for more student access to virtual and cloud-based labs. Other changes, such as recording fashion design demonstrations and posting the videos to be viewed online—as opposed to having students huddle around a student’s work in the classroom—assures that everyone gets a view and the ability to repeat the demo as needed. “I don’t think the classroom will ever be the same,” says Joanne Mitchell, Interim Assistant Provost. “We’re learning so much that will transform the education going forward.” As faculty prepare for a hopeful return to campus this spring—the decision about which has not yet been made by the administration as it awaits public health guidance—the different programs are also exploring how blended classes might work for the future.

“I don’t think the classroom will ever be the same,” says Joanne Mitchell, Interim Assistant Provost. “We’re learning so much that will transform the education going forward.”

In writer and collaborative artist Emma Kemp’s Foundation studio classes, the remote environment has had some benefits. Typically, students working with various materials display their work in the studio, where peer review plays a crucial part of the design process. “Because we’re having to wrestle with how we present and display our work in a more profound way than in the studio, all of these possibilities have opened up,” Kemp says. “We’re looking at ways in which the photographic rendering of the work is a consideration earlier in the design phase, which raises interesting questions in terms of the crux of the design itself. We have these foundations for what makes design successful, but now we’re acknowledging that the design needs to be accessible for the screen. Arts education is catching up to contemporary experiences of viewing—how art is being experienced culturally and socially—and as artists we are having to respond.”

Increasingly, professional designers are working independently and remotely from home studios, and often in different time zones from their clients. Alternative Materials and Processes instructor Lorenzo Hurtado sees the virtual classroom as a valuable opportunity for preparing his students for these professional realities. “The great advantage of remote learning is that students are experiencing the professional way of presenting, delivering, and sharing work and preparing portfolios,” he says. “Traditionally, student work is done under faculty supervision in the classroom, and faculty gives feedback. But now that feedback happens in the student’s own setup, much as it would in a professional environment. As a result, this semester, we’re seeing many more professional practice questions coming up.”

“The great advantage of remote learning is that students are experiencing the professional way of presenting, delivering, and sharing work and preparing portfolios.”

Pivoting to meet the moment is an ability in which Patricia Kovic excels. In her interdisciplinary teaching practice in the Product Design, Communication Arts, and Creative Action programs at Otis, she serves as the lead faculty for an experimental teaching laboratory. “Like many of us, when the pandemic hit, we had to adjust quickly,” says Kovic, who has been writing and researching about the future design of education along with co-teacher Blanka Domagalska, and in so doing developed a new project for students called “Knowledge Kitchen.” The model focuses on micro-learning modules— easily viewable on a mobile phone—which act as “discrete bursts of information so small that they are delivered in under a minute.” Production time to create the modules is minimal and allows for playful and creative communication, she says. Kovic and Domagalska have welcomed a variety of guests into their virtual classroom, including architects, toy and product designers, people who work in the fashion industry, and even an astronaut, all creating an innovative environment for nimble problem-solving and adjusting to ever-changing circumstances. “In this new world, uncertainty is our guide and friend and, worst-case scenario, what we need to build for,” Kovic says.

Graphic designer and writer Silas Munro builds his curriculum not only to engage with current dilemmas relating to the pandemic, but to create more inclusive design practices for the future. “Not only are we dealing with COVID and remote learning, we’re dealing with a reckoning with white supremacy and what has traditionally been a very limited canon,” says Munro, whose work considers the often unaddressed post-colonial relationship between design and marginalized communities. This semester, students in Munro’s graduate typography class are designing publications using Hangul, the Korean alphabet. “Particularly with typography, which is biased toward the Latin letter, I’m having students look at type as form by working with an alphabet, that is not their native alphabet, to realize that typography is not just Western and European.”

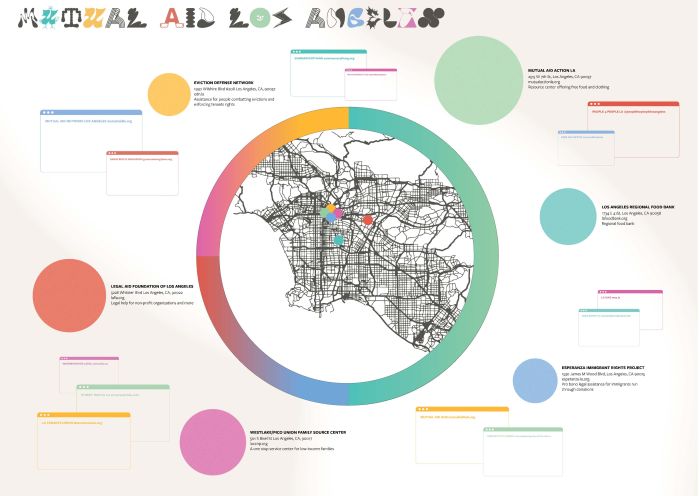

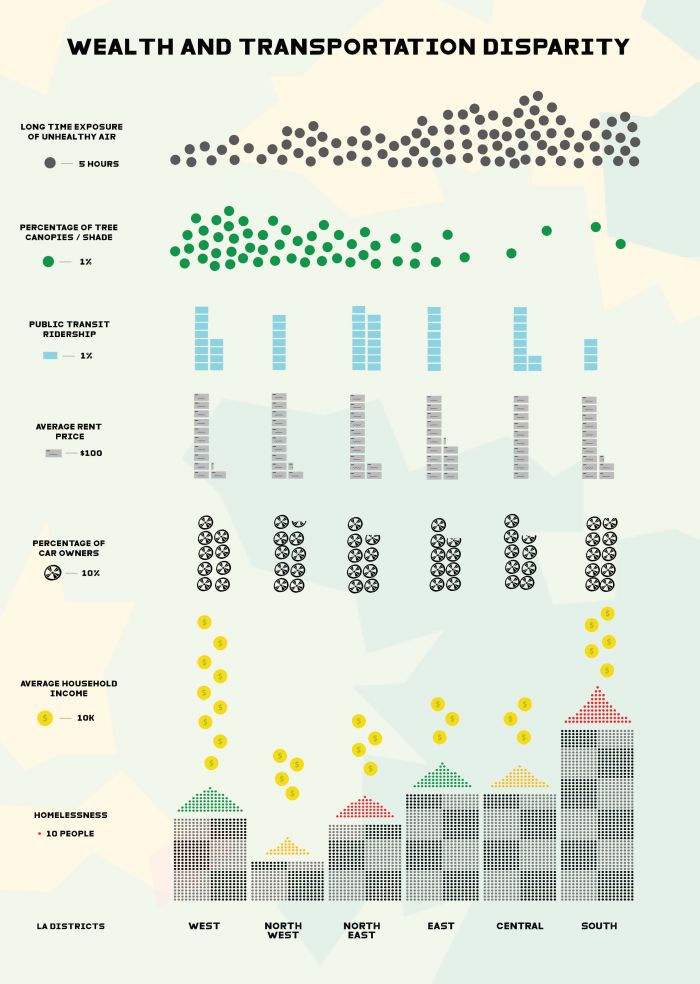

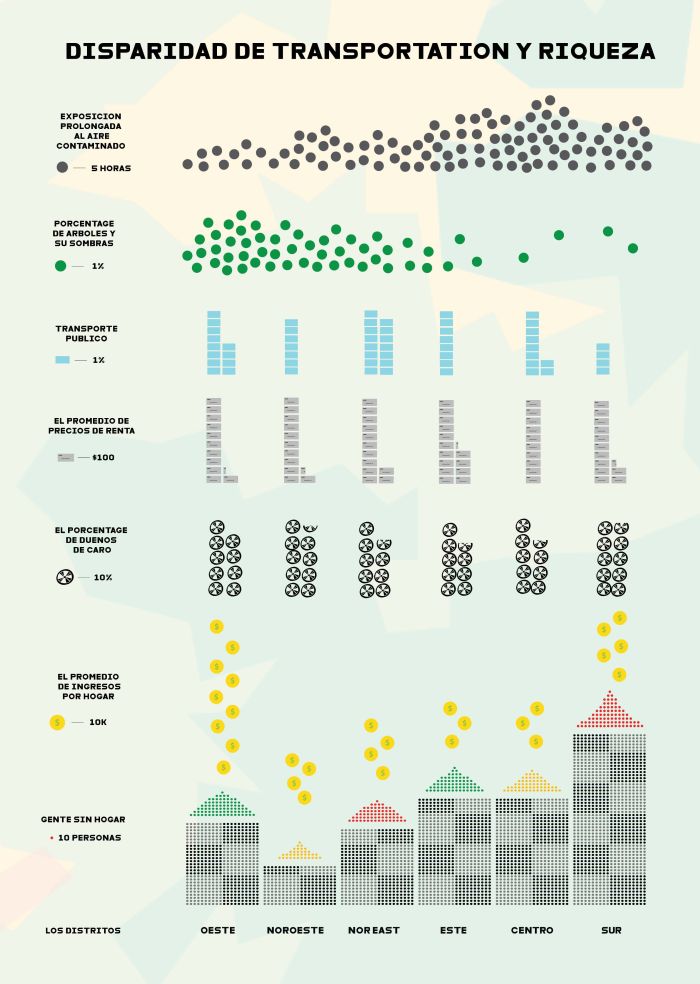

Munro sees an increased sense of urgency from students to create work with significance. “Students are really invested and their expectations are high,” he says. In his Communication Studio III class, one junior made a map of mutual aid organizations that have sprung up in Los Angeles in response to the social unrest following George Floyd’s murder over the summer by police officers in Minnesota. “The map was so thoughtful and timely and beautiful,” Munro says. “Another group made a bilingual map looking at public transit, median income home prices, and air quality in a neighborhood that showed L.A. in this very complex way, taking these things that feel overwhelming, but painting a picture of where we need change.”

Now, more than ever, teachers are committed to creating bonds between students in the virtual classroom. “You have to design that engagement into the class,” says Munro, who incorporates a “council” or space where students can share feelings at the beginning of each class. “The councils have become a lifeline for my group. It’s been super helpful learning that they can trust each other and share the good, the bad, and the ugly.”

Kemp uses writing to encourage a sense of intimacy between her students. “I start most classes off with a writing prompt, something reflective for sharing,” she says. “It seems really important to begin with every single person in the class sharing something, whether that’s a favorite song they’re all obsessing over, or a current event. The students are showing such curiosity and inquisitiveness, and it’s been incredibly positive so far.”

With faculty members at the forefront of reimagining an arts education, the benefit to students is tangible in their work, as they learn new ways to think critically and problem-solve in a remote learning environment, using creativity, innovation, and vision. “COVID-19 forced innovation,” Takayama-Ogawa says. “Invention was borne out of need. At the end of each week I am grateful—grateful for the chance of a lifetime to educate students in new ways never imagined.”